Understand What “Australian Standard Fire Doors” Actually Mean

Many people assume a fire door is simply a heavier door that slows down flames. That idea is understandable, but it is far too narrow for how fire doors work in Australia. On local projects, I often see builders treat them like upgraded timber doors—until the certifier points out gaps that are too big, hardware that wasn’t approved, or a missing tag that stops the whole floor from passing inspection. Once you’ve been through that experience, you realise a fire door is less about a single component and more about a system that has to work as one piece.

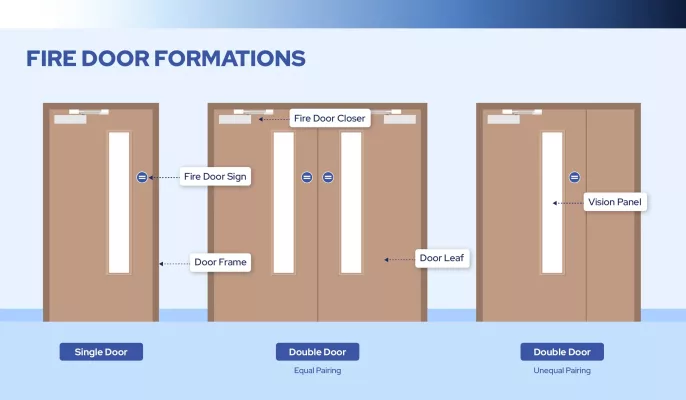

Fire doors as a system, not just a leaf

An Australian standard fire door includes the door leaf, the frame, the seals, the hardware and the way the entire set is installed. If any one piece is changed, the performance can shift from compliant to questionable very quickly. The simplest example is hardware: a fire-rated hinge or closer isn’t something you upgrade for aesthetics. It must be the same type that was used in the original test or listed in the approved hardware schedule. I’ve seen cases where a site team swapped a compliant closer for a softer-closing decorative model. The door still “looked” fine, but the set was no longer compliant, because the closing force changed and the seal contact couldn’t be guaranteed.

Compared with a standard interior timber door, a fire door has a core designed to hold integrity for a rated period, usually with pyro-expanding seals that swell under heat. The frame is heavier, the hinge plates are thicker, and even the screw length matters. When you see the door purely as a barrier, you miss all the details that actually make it reliable during a fire.

How NCC and AS 1905.1 tie together

The rules behind these doors come from a few places, but the logic is straightforward once you’ve seen how they overlap on real jobs. NCC sets the broader requirements for fire compartments and where fire doors must be used. It answers the “where” and “why.” AS 1905.1 then steps in to define what a compliant fire door set actually looks like—dimensions, construction, allowable gaps, acceptable hardware, fixing methods and the test evidence that supports it. AS 1530.4 relates to the fire test itself, which tells you how long the door maintains integrity and insulation in a controlled burn.

When these documents line up, the process feels clean. When they don’t—such as when drawings show a certain FRL but the supplied door has a different tag—the project stalls. I’ve seen this happen on a medium-rise apartment block in Melbourne where the contractor installed doors that were tested for a different wall type than the one used on site. The doors were not “bad,” but they did not match the conditions of the test, and the certifier rejected the entire batch. A week of rework could have been avoided if the team had matched the intended wall type to the test evidence earlier.

YK Door Industry (Yuankai) has gone through the full AS 1905.1 testing cycle more than once, particularly for 1-hour and 2-hour door sets commonly used in commercial sites across NSW and QLD. A few of our doors went into a refurbishment project in Perth’s industrial zone last year, where the client needed steel frames paired with specific smoke seals to meet the fire engineer’s plan. The paperwork mattered just as much as the hardware, because the certifier wanted a clean chain between the test report, the approved hardware list and the onsite installation photos.

A practical definition that makes sense on site

If we strip away the jargon, an Australian standard fire door is a door set that has been tested as a complete system, approved under AS 1905.1, installed according to that test evidence, and labelled so an inspector can confirm everything matches. It’s not the weight of the leaf, the thickness of the core or the brand of the hinge that makes it compliant—though all of these matter. It’s the fact that every part is working in the same configuration that survived the fire test.

From a practical viewpoint, compliance outweighs theoretical performance every time. During a fire, what matters is whether the door closes properly, seals engage, gaps stay within limits and the structure holds long enough for evacuation. During an insurance claim or council inspection, what matters is whether the documentation and installation match the standard. You can have a beautifully made door, but if the tag is missing or the wrong lock was fitted, it simply won’t pass.

Understanding this early saves time, avoids rework and gives you something far more important than a heavy door—predictability when it counts.

Know the Core Standards: NCC, AS 1905.1 and AS 1530.4

When people first look into fire door requirements in Australia, the number of standards can feel overwhelming. In practice, there are only three you need to keep in mind: NCC, AS 1905.1 and AS 1530.4. You don’t have to memorise every clause to run a project well. You just need to know which document answers which question. Once you understand the role of each standard, the entire process—from design to installation to certification—starts to feel far less tangled.

NCC – the big picture for fire compartments

The NCC sits at the top of the decision chain. It doesn’t tell you how to build a door; it tells you where fire doors are required and why. It lays out the logic of fire compartments, escape paths, riser shafts, and any opening that must maintain integrity for a certain period. When a fire engineer or architect places a fire door symbol on a drawing, they’re translating NCC obligations into practical layouts.

One thing I’ve seen repeatedly on Australian sites is that teams focus heavily on the door leaf and forget the wider context. A fire door is only there because the NCC says this particular opening must resist fire for a defined time. That means the door’s FRL, wall type and hardware selection are all consequences of that upstream decision. When you see it this way, the “big picture” becomes much easier to navigate.

AS 1905.1 – the rulebook for fire door sets

If you only remember one number, make it AS 1905.1. It is the standard that defines what a compliant fire door set actually is. It covers the construction of the leaf, the type and thickness of the frame, the allowable clearances, the hardware combinations, the fixing methods and the way the whole assembly must behave when installed. It is not a “suggestion”; it is the document certifiers lean on when determining whether something passes or fails.

In my experience, a lot of site issues don’t come from poor manufacturing but from deviations from this standard. A contractor might shave a few millimetres from the door bottom to clear uneven flooring, or they might swap hardware without checking if it sits on the tested schedule. The door can still swing, close and look perfectly fine, yet it no longer matches AS 1905.1 requirements. On a project in Brisbane a few years ago, a batch of doors supplied by a different vendor had the right FRL but were hung with non-listed hinges. Nothing looked wrong, but the certifier still rejected them because the hinge plates didn’t match the tested configuration. A day of rework could have been saved if the team had simply cross-checked the schedule.

YK Door Industry (Yuankai) has supplied AS 1905.1–compliant door sets to a few regional warehouse and hotel refurbishments in Australia, and the conversations with certifiers often revolve around the same things: leaf construction, hardware compatibility and whether the frame and wall type match the tested evidence. The standard brings clarity, but only when everyone refers to the same page.

AS 1530.4 – how fire doors are actually tested

AS 1530.4 is where the fire test itself lives. It describes how the door is burned, how temperatures are measured, and how long the assembly maintains integrity and insulation during the test. This is the standard that determines the FRL you see on drawings—like -/60/30 or -/120/60.

What surprises many people is that a fire test is not a test of “materials” alone; it is a test of the entire door set, including the frame and hardware. Change the frame thickness, the hinge model, or the closer settings, and the performance may shift. Different wall types also influence results, which is why a door tested on a block wall cannot automatically be installed on a plasterboard wall unless the test evidence covers both situations.

I once saw a case on a Sydney project where the door itself had been tested correctly, but the installer substituted a different type of intumescent seal because the original one was out of stock. That single change broke the chain of evidence. The certifier didn’t question the manufacturer; they questioned the installation because the site condition no longer reflected the tested configuration under AS 1530.4.

Why drawings, certificates and on-site work must match

Most of the real project pain comes from mismatches between what the drawing says, what the certificate covers and what actually gets installed. A designer may specify an FRL that doesn’t match the selected wall type. A door manufacturer might supply a certificate that covers only certain hardware combinations. Then the site team might install something slightly different because of availability, lead time or a last-minute change. Each step introduces a small deviation, and by handover, the certifier is faced with three different versions of “truth.”

In my view, the simplest way to avoid this is to treat those three documents—the drawings, the test report and the as-built condition—as a single chain. If any one link changes, you check the others. People sometimes worry this slows the project down, but from what I’ve seen on Australian sites, it usually saves time. Reworks, rushed replacements and failed inspections cost far more than a brief, early conversation to align all three.

Understanding how NCC, AS 1905.1 and AS 1530.4 fit together won’t turn you into a fire engineer, but it will give you a working map of the system. And with fire doors, having that map makes the difference between a smooth sign-off and a week of avoidable fixes.

FRL Ratings and Door Tags – How to Read Them Without Guessing

One of the most common questions on site is, “How many minutes is this fire door?” People look at the thickness of the leaf or the weight of the door and try to guess its rating. In Australia, guessing is the fastest way to lose time during inspections. Fire doors tell their own story through the FRL rating and the door tag fixed to the leaf. Once you know how to read both, you’ll never need to rely on assumptions again.

What FRL numbers actually tell you

Australian FRL ratings are written in a three-part format, such as -/60/30 or -/120/60. The three numbers represent structural adequacy / integrity / insulation. Fire doors don’t carry load, so the structural number is usually a dash. The other two numbers matter far more on day-to-day projects.

Integrity (the middle number) describes how long the door can stop flames from breaking through.

Insulation (the last number) measures how long the door can limit heat transfer to the other side.

If a door is tagged -/60/30, it means the door held back flames for 60 minutes, and limited heat rise for 30 minutes during the AS 1530.4 test. On most commercial and residential jobs, builders focus almost entirely on those two numbers because they reflect the risks certifiers care about: flame spread and heat transmission.

I often tell contractors that if they only remember the basics, keep an eye on the last two digits. They tell you more about real-world performance than the thickness of the door ever will.

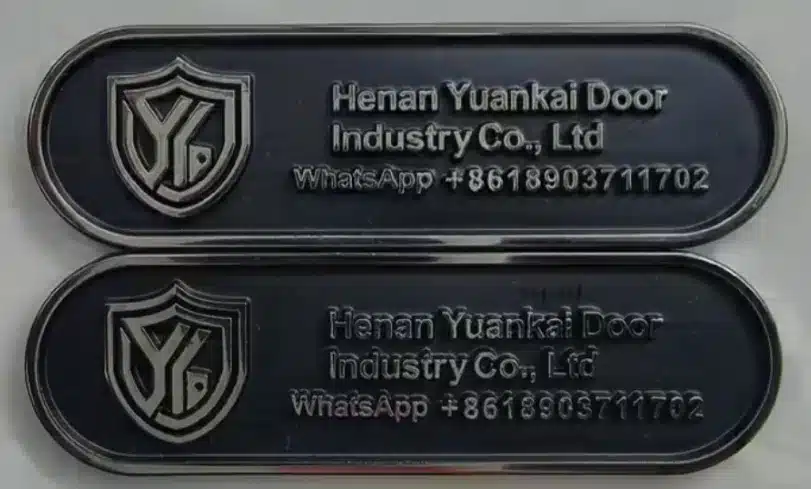

What should be on a compliant fire door tag

A compliant Australian fire door always has a fixed metal label or tag attached to the leaf—usually near the hinge edge. The tag identifies the exact set that went through fire testing and links the installed door back to its certification. When the tag is missing, inspectors don’t have anything to verify against. In my experience, a door without a tag is almost guaranteed to attract scrutiny.

A proper tag should include:

- the manufacturer’s name,

- the test or certificate number,

- the FRL rating,

- the year of manufacture,

- and sometimes the model or door type used in the original test.

If you’re not sure whether a tag is legitimate, check if the information can be traced back to the AS 1905.1 test evidence. A tag that doesn’t lead anywhere is as unhelpful as no tag at all.

YK Door Industry (Yuankai) uses permanent stainless steel tags with engraved test numbers so they don’t fade or peel over time. You can check the sample tag below once the image is uploaded.

From a practical standpoint, the tag protects everyone: the installer, the certifier, and the building owner. Without it, you’re relying on memory, and on complex projects that’s never enough.

Quick checks you can do during a site walk

During inspections, I’ve found that a few simple habits make a huge difference. The first is taking clear photos of every door tag before the ceiling closes or furniture arrives. It takes minutes and often resolves arguments later when paperwork goes missing or teams change over. The second is matching the FRL on the tag to the one on the drawings. You’d be surprised how often the two don’t align, especially in refurbishments where the design changes halfway through.

Another tip is to look at the position and condition of the tag itself. If it’s crooked, loose, or looks recently replaced, I take a closer look. Tags shouldn’t be swapped or moved once the door leaves the factory. On one Sydney retail fit-out, the certifier stopped the handover simply because three tags appeared to be newly riveted. It turned out the supplier had re-tagged doors after a mix-up—not maliciously, but still outside compliance. A full replacement batch had to be ordered.

As a general rule, if a fire door set has a clean tag, a matching certificate and an FRL that aligns with the drawings, the inspection usually goes smoothly. If any one of these three is missing, the conversation tends to get longer—and more expensive.

Fire Door Hardware Is Part of the Tested System, Not an Afterthought

A lot of problems on Australian projects don’t start with the door leaf or the frame—they start with the hardware. Hinges, closers, locks, latches, smoke seals, automatic door bottoms and even fixing screws are part of the tested fire door system under AS 1905.1. When any piece is swapped, the chain that links the door back to its fire test under AS 1530.4 breaks. I’ve seen beautiful sets of doors fail inspections simply because someone on site decided a different handle looked “more modern.” The door might still close, but it’s no longer the same door that passed the test.

Why hinges, closers and locks must match the test

Hardware is not decorative on an Australian standard fire door—it’s functional and evidence-based. The hinges must support the leaf under fire load, the closer must pull the door shut with enough force to engage the seals, and the lockset must survive heat long enough to maintain integrity. All of this was proven during the fire test, and those test conditions are specific.

When a certifier checks a fire door, they don’t only scan the door tag. They look at hinge count, hinge size, closer strength, lock body shape and whether smoke seals match the approved schedule. If any piece isn’t listed in the AS 1905.1 test evidence, the whole set becomes questionable.

On a job in regional NSW, I watched a contractor replace tested hinges with soft-close designer hinges right before handover. The doors still looked compliant, but the certifier immediately picked up the mismatch. The replacement hardware was never part of the original test, so the FRL rating could no longer be relied on. The team spent the next two days re-hanging every door.

I often say that if you are going to protect your budget, protect the hardware. It affects compliance more than the veneer, the paint colour or the handle style ever will.

Common hardware mistakes on Australian sites

The most persistent mistake is swapping hardware late in the job. Sometimes it happens because the interior designer wants a different finish; sometimes a supplier delivers the wrong batch; sometimes a site supervisor just prefers a different handle. Whatever the reason, “looks better” usually translates to “not tested.”

Another issue is mixing hardware brands. Builders often assume that if each individual item is fire-rated, the whole set is automatically compliant. The Australian system doesn’t work that way. A closer tested with a certain lock might not behave the same with a different lock body. Smoke seals from another supplier may expand differently and compromise the closing force.

I remember a refurbishment in Melbourne where the doors were fine, but the installer switched to non-listed graphite seals because they were cheaper. The seals expanded too quickly in heat, pushing the leaf out of alignment during the certifier’s review. The doors had passed the furnace test in their original configuration, but the on-site configuration was now completely different.

And then there’s the issue of screw length. It sounds minor, but AS 1905.1 hardware schedules often specify minimum screw penetration. Shorter screws can loosen under heat. Certifiers in Australia do check this—especially after a few well-known failure cases in older buildings.

Simple rules of thumb when selecting hardware

There are a few habits that consistently reduce risk:

Match everything to the approved hardware list.

Every Australian standard fire door comes with a hardware schedule linked to its AS 1905.1 certification. Treat that list as non-negotiable. If you want to change something, confirm it with the manufacturer and get written evidence.

Check the hardware before installation, not after.

Many reworks happen because someone discovers mismatched hinges only once the door is already hung. A five-minute check in the storage room saves hours on site.

Keep to the same brand and model when possible.

Mixing components increases the chance of conflicting performance. The tested configuration is always the safest path.

Photograph the hardware once installed.

This isn’t about covering yourself; it’s about having evidence when the certifier or the fire engineer asks why a certain closer or latch was used. Clear photos have resolved more disputes than any specification note.

From what I’ve seen across Australian commercial and residential projects, changing hardware is one of the top three reasons fire doors fail inspections. If the budget is tight, make savings elsewhere. Hardware is not the place to experiment.

Installation Details Can Make or Break Compliance

Most people think the quality of a fire door starts in the factory. In reality, a big part of its performance is determined on site. An Australian standard fire door can be perfectly manufactured, fully compliant under AS 1905.1 and tested under AS 1530.4, yet fail an inspection because of a few millimetres of installation error. The gap under the leaf, the wall type behind the frame, the fixing pattern—all of these shape how the door holds up during a fire. From what I’ve seen, installation is where many projects lose time, money and patience.

Wall types and fixing methods

Fire doors do not behave the same in every wall. A frame installed in a concrete wall carries heat differently from one installed in a plasterboard shaft wall. AS 1905.1 test evidence usually links door sets to specific wall types, and that’s where a lot of mismatches happen. If the manufacturer tested the door on a block wall but the project uses a lightweight stud wall, the test evidence might not apply. Certifiers in Australia are very strict about this, because the wall influences the entire fire performance of the opening.

Fixing methods matter as well. Frames must be anchored at specific points, and the gap between the frame and wall must be packed with fire-resistant material. I’ve seen installers use construction foam because it expands easily, but in many cases standard foam is not acceptable for fire-rated openings. The right material depends on the test configuration: sometimes fire mortar is required, sometimes mineral wool, sometimes a particular fire-rated foam approved by the manufacturer.

On a warehouse project in Perth, a crew installed frames with inconsistent fixing points because the substrate wasn’t perfectly plumb. The doors looked straight, but the certifier failed the lot because the fixings didn’t match the tested setup. A few extra minutes spent levelling the opening would have saved an entire day of rework.

Gaps, seals and thresholds that actually work

Gaps around the door leaf are one of the first things a certifier will check. Under AS 1905.1, there are maximum clearances for the head, jambs and bottom of the leaf. Exceed those limits—even by a few millimetres—and the fire door no longer behaves as tested. That’s why “site trimming” is such a common source of trouble. Installers shave the door to accommodate uneven floors or misaligned frames, but every millimetre removed changes the sealing pattern.

Thresholds play a role too. On many Australian jobs, particularly in high-traffic areas, automatic door bottoms are required. If the bottom seal doesn’t make consistent contact with the floor, smoke tightness and thermal insulation drop immediately. I’ve inspected doors where the seal only touched the floor on one side due to sloping tiles. The door still “closed,” but it wasn’t doing the job expected under fire conditions.

Smoke seals must also remain intact. I’ve seen seals cut or removed during painting, or damaged when door stops are installed. Once the intumescent strip is compromised, the door no longer matches the tested configuration—even though the leaf and frame themselves are fine.

What inspectors usually look at first

Certifiers and fire engineers develop sharp instincts after years of site visits. They rarely start with paperwork; they start with physical clues. The first things they tend to check are:

- the bottom gap,

- the alignment between the leaf and frame,

- whether the seals are continuous and undamaged,

- and whether the frame packing matches the test evidence.

One certifier I worked with in Melbourne used to lightly tug on the frame. If it shifted even slightly, he would call for the wall interface to be reopened. That might sound harsh, but once you’ve seen how heat warps a door under pressure, you understand why installation matters just as much as manufacturing quality.

Another pattern I’ve seen is that installations done in a rush—especially near the end of a project—tend to fail more often. Doors installed early and checked before finishes go in typically pass smoother. The difference is simply time: when installers aren’t rushed, they follow the AS 1905.1 installation details more faithfully.

A practical takeaway

If you want an Australian standard fire door to pass inspection the first time, treat installation as part of the system, not a finishing task. Plan for the right wall type, confirm the fixing method, monitor the gaps and protect the seals. These details don’t just satisfy the certifier—they ensure the door performs as tested when it matters.

Maintenance, Damage and Upgrades – Fire Doors Are Not “Fit and Forget”

A lot of people assume that once an Australian standard fire door is installed and signed off, it will protect the building for the next twenty years without much attention. In practice, fire doors age just like any other building component. Everyday use, repeated impacts, humidity, poor cleaning habits and small modifications can all weaken performance. What makes this particularly risky is that the damage is often subtle. The door may still close and look fine, but the performance that once passed AS 1530.4 testing is no longer guaranteed.

Everyday damage that compromises fire doors

Walk through any busy corridor in an apartment building or hospital and you’ll quickly see how fire doors get worn out. Hinges loosen, seals peel off, closers leak oil, and door bottoms drag across uneven floors. Tenants wedge doors open for airflow or convenience, and cleaners sometimes prop them open with bins while working. None of these actions are malicious, but they all pull the door further away from the condition it was tested under.

One of the most common issues I see is seal deterioration. The intumescent strip dries out or gets cut during repainting. Even a few centimetres of missing seal can cause smoke leakage, and smoke tightness is one of the first things a certifier will question.

Another quiet killer is door leaf warping, especially in older buildings with fluctuating humidity. A warped leaf creates uneven gaps, and once those gaps exceed the AS 1905.1 clearance limits, the door can no longer perform as intended. I saw this on a retrofit project in Adelaide where a 15-year-old door looked perfectly serviceable, but the bottom gap had grown to nearly 14 mm because the leaf had bowed. Repainting it didn’t solve anything—the door had to be replaced.

Basic checks facility managers can do

You don’t need to be a fire engineer to keep Australian fire doors in good shape. A simple routine check once or twice a year can prevent most failures. The three things I tell facility managers to look for are:

Does the door close smoothly and fully every time?

If the closer hesitates or the latch doesn’t engage, that’s a warning sign.

Are the seals continuous and undamaged?

Look for cuts, missing segments, or seals that have been painted over.

Are the gaps still within limits?

You can do a basic check with a 3 mm and 10 mm gauge. Anything beyond that needs attention.

One facilities team in a Brisbane hotel told me they saved thousands of dollars simply by doing a quick quarterly walk-through with a checklist. They caught multiple issues—missing screws, loose hinges, worn seals—long before the annual audit.

When it’s time to call a specialist

There are moments when a quick check isn’t enough, especially in older buildings or when modifications have been made over the years. Installing a door viewer, drilling a cable hole for access control, replacing a lock body with a “nicer” one, trimming the leaf to suit new flooring—all these changes can void the original certification.

A real example:

On a project in Western Australia, YK Door Industry (Yuankai) supplied AS 1905.1-compliant fire doors for a warehouse office upgrade. Two years later, the building manager called because a tenant had installed a new access control reader by drilling into the leaf. The hardware installer didn’t realise it was a fire door. By the time we saw it, the modification had cut into the core in a way that wasn’t covered by the test evidence. The door still worked mechanically, but it no longer matched its tested condition. The safest option was replacement—not because the door was poorly made, but because alterations broke the compliance chain.

This kind of situation is more common than people think, especially in mixed-use or high-turnover buildings.

A practical viewpoint

The truth is simple: Australian standard fire doors will protect people when they’re maintained, and they become liabilities when ignored. Damage doesn’t announce itself loudly. A loose screw here, a worn seal there, a door that doesn’t quite latch—these are the signs that matter.

If you’re responsible for a building, don’t treat fire doors as “installed and done.” Treat them as critical safety equipment with a life cycle. A few routine checks and timely repairs cost far less than a failed audit—or a door that doesn’t perform when it’s needed most.

Maintenance, Damage and Upgrades – Fire Doors Are Not “Fit and Forget”

One of the biggest misunderstandings about Australian standard fire doors is the belief that once they’re installed and signed off, they can be left alone for decades. In reality, fire doors age just like anything else on a building. Hinges loosen, seals tear, closers leak, and tenants wedge doors open because they get tired of them swinging shut. I’ve seen perfectly compliant door sets turn into liabilities within a year simply because no one checked them after handover. Fire doors are built for emergencies, but they only work if they’re maintained.

Everyday damage that compromises fire doors

Most of the damage I see on site doesn’t come from dramatic events; it comes from ordinary daily use. Doors in car parks get hit by trolleys, doors in apartments get slammed, and doors in commercial corridors get propped open with bins or wedges. Each small act chips away at the door’s ability to close properly and hold its FRL rating under fire.

Smoke seals are often the first to go. Painters remove them, cleaners tear them, or tenants peel them off because they think they’re decorative strips. Once the seal is damaged or missing, the door no longer behaves the way it did under AS 1530.4 testing. I’ve come across doors where the entire intumescent strip was painted over, making it stiff and unable to expand properly in heat.

Hardware suffers quietly too. A closer may leak oil for months before anyone notices. Hinges can sag, especially on heavier -/120/60 doors. A lockset might become loose from repeated use. On one job in Queensland, a closer on a stairwell door was leaking so slowly that no one raised it during quarterly checks. But by the time the certifier came around for the annual audit, the door could no longer latch at all.

During a refurbishment project in WA, a set supplied by YK Door Industry was still structurally sound after several years, but the building manager asked for a review because tenants had complained about “heavy closing.” It turned out the issue wasn’t the door—it was the closer arm, bent by repeated force from people trying to hold the door open. A simple hardware replacement brought the door back to compliance. The door leaf itself was fine; the daily use was not.

Basic checks facility managers can do

You don’t need to be a fire engineer to spot a non-compliant door. A quick walk-through by a facility manager can uncover most of the issues long before a certifier arrives.

The first thing to check is whether the door closes and latches by itself from any open position. If it doesn’t, the closer or hinges need attention. Then look along the seals: are they continuous, soft, unpainted and firmly bonded? Check the bottom gap—if you can slide more than two fingers under the leaf, it might already be outside AS 1905.1 clearances.

I also suggest looking at signs of tampering. Extra screw holes near the lock body, fresh paint on the seals, or mismatched hinges usually signal an unapproved change. These small clues often point to bigger compliance issues.

What I often tell building owners is this: you don’t need to do a technical inspection; just focus on how the door behaves. If something feels off—slamming too hard, not latching, dragging on the floor—it’s worth getting a professional in. Most problems are cheaper to fix early.

When it’s time to call a specialist

There are moments when a simple check isn’t enough. You should involve a fire door specialist when:

- a door has been visibly damaged, especially around the core or the edges,

- seals are missing or unrecognisable,

- hardware has been changed without documentation,

- the building layout has been altered and doors no longer sit where they originally did,

- or when preparing for annual audits required under fire safety regulations in your state.

In older buildings, upgrades can be complicated. Many doors were installed under earlier versions of the NCC or older AS 1905.1 requirements. I’ve had to tell clients that certain older doors cannot simply be “patched” because the core or hardware no longer aligns with current evidence. Sometimes a partial replacement works; sometimes the safest path is a full door-set renewal.

If your building has seen heavy use, renovations, tenant turnover or long periods without inspection, don’t wait for an emergency to reveal weaknesses. Fire doors don’t fail dramatically—they drift away from compliance quietly, in small, incremental ways.

Documentation and Certification – What You Should Always Keep on File

On Australian projects, a fire door is only as credible as the paperwork behind it. You can have a perfectly installed AS 1905.1 door set, but if the documentation trail is incomplete or inconsistent, certifiers will hesitate—and they have good reason to. Fire doors rely heavily on traceability. The drawings, certificates, test evidence and installation records form a chain that proves the door is the same system that passed the AS 1530.4 fire test. Break that chain, and you’re relying on assumptions rather than evidence.

Certificates, test reports and what they prove

The first document worth understanding is the AS 1905.1 compliance certificate. It outlines the door’s construction, hardware, frame type and the test evidence that supports the design. Contractors often think the certificate is “just paperwork,” but to certifiers, it’s the primary proof that the installed door is not a random combination of components.

Then there’s the AS 1530.4 fire test report. Most projects don’t need the full report—it can be hundreds of pages long—but you should have access to the summary that shows the tested configuration, wall type, hardware schedule and FRL result. When builders compare this summary with the drawings, they can catch mismatches early, especially on refurbishment jobs where existing walls may not match the test evidence.

Finally, the manufacturer’s compliance tag on the door leaf ties everything together. The tag shows the test number, FRL rating and manufacturer identification. If a tag on site doesn’t match the certificate, or if certain details can’t be traced to the test evidence, the discussion becomes complicated quickly.

I recall a job in South Australia where the certifier paused handover because a few door tags listed a test number that wasn’t in the paperwork the builder submitted. It turned out the doors were correct and the paperwork was simply outdated, but the delay cost the team two days. A small document mismatch created a full-site stop.

Simple ways to keep your fire door records organised

Most compliance headaches come from missing or scattered files. Builders often keep certificates in emails, test reports in a separate folder, and installation photos on someone’s phone. Months later, when the certifier asks for a record, no one remembers where anything is. A little organisation early on saves hours later.

On several projects I’ve supported—including one where YK Door Industry supplied AS 1905.1-compliant door sets for a logistics facility in WA—the smoothest audits happened because the builder kept all door documents in a single shared folder: certificates, test summaries, hardware schedules, delivery dockets and a few installation photos. It wasn’t fancy; it was just organised. Certifiers don’t need glossy binders—they need clarity.

My rule of thumb is simple:

If a document helps prove what was installed, keep it.

If it shows the door, the hardware, the wall, or the installation method, it belongs in the folder. Digital storage has made this incredibly easy.

Another habit that pays off is photographing the door tag and the installed hardware before ceilings and trims go in. A 10-second photo can settle disputes months later about what was actually used on site.

What certifiers usually ask for during inspections

If you’ve been through a few Australian certification processes, you’ll notice inspectors tend to ask for the same documents repeatedly:

- The AS 1905.1 certificate for the exact door type used

- The hardware schedule that shows hinges, closers, locks and seals

- The FRL rating listed both on the drawings and on the door tag

- Any test evidence linking the door set to the wall type on site

- Installation photos, especially around the frame packing and seals

Certifiers aren’t trying to make life difficult. They’re verifying that the system installed on site is the same system that survived the fire test. If anything doesn’t line up—test numbers, wall types, hardware models—they are required to question it.

One certifier I’ve worked with in NSW used to say, “Show me the story.” He wanted to see the chain: the drawing → the certificate → the test evidence → the door tag → the site condition. When all five align, sign-off is quick. When one of them doesn’t, the conversation gets long.

A practical takeaway

Documentation is not a bureaucratic burden; it’s the backbone of compliance. A well-maintained folder of certificates, photos and hardware records can save a day—or even a week—when a certifier conducts a final check. It also protects building owners, because if a fire incident ever occurs, investigators will look first at whether the installed door matches its certified configuration.

If you treat documentation with the same care as installation, you’ll find that fire door compliance becomes predictable rather than stressful.

Final Thoughts – Understanding the Australian Fire Door Landscape

Australia’s fire door market is shaped less by brands and more by accountability. Whether a door comes from a major local manufacturer or a smaller overseas supplier, it enters the same system of standards, inspections and long-term responsibilities. That system—built around the NCC, AS 1905.1 and AS 1530.4—tends to reward clarity, evidence and consistency rather than marketing or appearance.

What becomes clear after working through enough projects is that the challenges are usually practical, not technical. Doors fail because someone trimmed the leaf to fit uneven flooring, swapped hinges late in the job, installed a frame in the wrong wall type or lost the paperwork needed for sign-off. These aren’t glamorous problems, but they’re the ones that determine whether a building passes inspection or ends up in a cycle of rework.

If there is one pattern across the Australian market, it’s that compliance gets easier when teams focus on the full system rather than individual parts. A fire door is not bought; it is built, installed, checked, documented and maintained over years. When any one of those stages is rushed or ignored, the risk shifts directly onto the builder, the owner or the occupants.

The projects that run smoothly usually share a few traits:

- the drawings match the certificates,

- the certificates match the door tags,

- the door tags match the hardware,

- and the hardware matches what was actually installed on site.

When these align, certifiers sign off quickly. When they don’t, the market feels unforgiving—because it has to be. Fire doors are one of the few building elements expected to perform perfectly on the worst day a building can face.

From small refurbishments in regional towns to high-volume apartment corridors in major cities, the underlying expectations remain the same: evidence over assumptions, function over appearance, and long-term reliability over short-term convenience. If your approach to fire doors follows those principles, the Australian market becomes far more predictable—and your projects become far easier to manage.