What Happened in Quezon City — A One-Hour Fire, Eight Lives Lost

Timeline & Building Profile

It started just past midnight in San Isidro, Galas, Quezon City. Most residents were asleep. The building was a three-story residential structure, and like many older homes in Metro Manila, it was largely made of wood and light interior partitions. Families lived close to one another. Hallways were narrow. Doors opened into shared corridors that doubled as everyday living space.

The fire began on the second floor. Neighbors recalled the smell of heat before they saw visible flames; by the time smoke pushed into the hall, the fire had already taken hold of the interior wood framing. Within less than an hour, the structure was engulfed. Eight people did not make it out. The official report later confirmed that most victims were found in rooms where the fire and smoke spread fastest.

This is not an unusual building type in the Philippines. It reflects dense living patterns, multi-family sharing of a single structure, and construction designed for affordability, not fire resilience. When you see this kind of building burn, you’re not surprised the fire moved fast. You’re heartbroken, because you understand why.

Why It Spread So Fast

Several factors layered together, turning a small ignition into a fatal event:

• Combustible Structure

Wood burns quickly. Once the wall and ceiling framing ignite, flames don’t just move—they travel through cavities where heat can’t be seen from the outside. By the time residents smelled smoke, the fire already had momentum.

• Nighttime Conditions

Most residents were sleeping. Reaction time becomes slower when every second matters. Even a one-minute delay in recognizing danger can decide survival.

• Narrow Circulation Spaces

The stairwell and central corridor were the only escape routes. When fire enters those spaces, the building turns into a trap. With heat building upward, the stairwell acted like a chimney, pulling flames and smoke through the structure faster than anyone could react.

• Lack of Compartmentation

There were no continuous fire-resistant barriers to slow the spread. One open door can be enough to let heat and smoke reach escape paths in seconds. That’s where the conversation about fire doors becomes real—not theoretical.

If a corridor door had been fire-rated and self-closing, if the stairwell had been separated as a protected escape core, residents on the upper floors may have had more time. Not guaranteed survival—but more time. And in a fire, time is everything.

Survivors’ Escape Route

One family on the third floor survived by climbing through a small bathroom window and dropping onto the roof of an adjacent home. They did not escape through the corridor. They escaped around the building’s designed exit path because the exit path was already lost.Think about that for a moment.The hallway should have been the safest direction.The stairwell should have been the way out.But once smoke and flame enter those spaces, escape reverses: people move sideways, through windows, onto balconies, over railings—anywhere except the official route.This is the emotional core of fire door conversations.Not technical. Not bureaucratic. Human.A fire door is not just a door. It is the difference between a hallway that remains passable for five extra minutes, and a hallway that turns into a tunnel of heat and smoke.When people hear “fire door,” they often picture a metal slab or a regulation checkbox in a construction document. But survivors do not think that way. Survivors remember what direction they could not run.That is the real cost we’re talking about here.

From News to Lessons — Where Fire Doors Fit in the Philippine Context

Fire Doors Aren’t Just Hardware

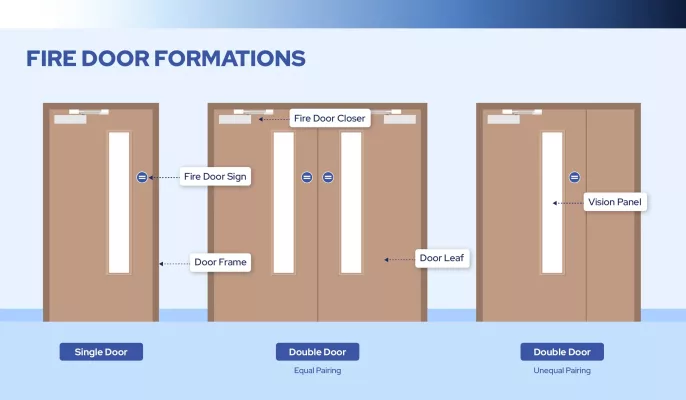

When most people hear the term fire door, the image that comes to mind is a heavy door—metal, solid, industrial-looking. Something you install because a contractor said so, or because the building permit requires it. But a fire door is not just a thick door. It is part of a system of time.

A fire grows fast. Smoke moves even faster.

A fire door is designed to slow down that movement.

A proper fire door does four things at the same time:

- It resists flame and heat long enough to keep a corridor or stair usable.

- It controls smoke, because smoke incapacitates before fire touches the body.

- It closes by itself, not left open by accident.

- And it seals tightly, especially at the gaps around the edges.

If any one of those elements is missing—if the door doesn’t latch, if the closer is disconnected, if the bottom gap is too wide—the barrier is technically there, but functionally gone.

This is why people say:

The fire door you prop open is the fire door you never had.

In the Philippines, especially in condos, boarding houses, dormitories, and mixed-use residential buildings, the hallway and the stairwell are the last safe spaces when a fire starts inside a unit. Once those spaces fill with hot smoke, evacuation turns into improvisation—people start jumping from windows, climbing onto adjacent roofs, or waiting for rescue in spaces that weren’t designed to protect them.

So the lesson is simple, but not easy:

A fire door is not a product you own. It is a barrier you must maintain.

If it does not close, it cannot save you.

If it does not seal, it cannot buy you time.

And time is the currency in every fire.

Exit Doors vs. Fire Doors

There is also a common misunderstanding: fire doors and exit doors are not the same thing.

They can overlap, but they do not serve the same purpose.

An exit door is about getting out of the building.

It must open easily, without keys or special knowledge. It should open in the direction of escape. Its priority is flow and accessibility.

A fire door, on the other hand, is about holding the fire back.

Its job is containment, not throughput. It stays closed. It separates the burning room or area from the corridors and stairs that people use to escape.

Sometimes, a single door must do both jobs. But that requires:

- A self-closing device so the door returns to the closed position automatically.

- A rated leaf and frame so the door actually buys time during a fire.

- Smoke seals so escape spaces remain breathable long enough.

In many Philippine buildings, the corridor doors are technically exit routes, but they are:

- wedged open for convenience,

- mismatched with non-rated replacement parts,

- or missing closers entirely.

In those conditions, the building might have fire doors on paper, but not in practice.

And that is how the safe route becomes the dangerous route.

When the corridor is protected, stairs stay usable longer.

When stairs stay usable, more people survive.

That is the entire principle.

Fire safety is not theoretical; it is mechanical and human at the same time.

A building either buys time, or it doesn’t.

The Rulebook — RA 9514 and IRR, and What BFP Looks For

The Philippines does have a clear legal framework for fire safety. Republic Act 9514, also known as the Fire Code of the Philippines, along with its Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR), outlines how buildings should be designed and operated to prevent the very kind of rapid fire spread seen in Quezon City. The Code does not only describe “what a building must have”; it describes how fire should be slowed, where people are expected to move, and what parts of the building must continue to function long enough for escape. In this sense, the Code is less about bureaucracy and more about physics and time management. Fire does not negotiate; it only accelerates. The Code exists to slow it down.

In actual enforcement, the Bureau of Fire Protection (BFP) focuses on several points that are directly relevant to fire doors and protected escape routes. First is compartmentation: corridors and stairwells must be separated from rooms and hazardous spaces by doors that can withstand fire and smoke for a defined period. Second is functionality: a fire door must close and latch on its own, not rely on someone remembering to shut it. Third is continuity: the protective barrier has to be consistent—if the wall is fire-rated but the door or frame is not, the barrier fails as soon as the weakest point fails. And finally, maintenance matters. Even a fully compliant fire door loses its purpose if it is propped open for ventilation, tied back for convenience, or its closer is removed because “it was too heavy to push.”

Compliance problems tend to repeat themselves across many Philippine buildings, whether residential, commercial, or mixed-use. A common issue is the “paper-compliant building”: the design drawings call for fire-rated doors, but the installed doors are ordinary hollow metal or wood, or the hardware has been replaced with cheaper non-rated components during renovation. Another recurring problem appears in everyday life: fire doors that are intentionally wedged open, especially in corridors without good ventilation. No law or certification can protect a building if the barrier meant to slow smoke is held open by a piece of cardboard or a plastic stool. It is not ill intent; it is habit, convenience, heat, airflow, or simply not understanding what is at stake. But the effect is the same: the door might as well not exist.

For building owners, property managers, and contractors, the practical takeaway is straightforward: compliance is not only a matter of choosing the right product, but of documenting and sustaining the system across the building’s life. When the BFP inspects, they look not just for the door itself, but for installation records, hardware lists, gap checks, closer performance, and whether the door is being used as intended. A compliant fire door is not defined at purchase; it is defined at inspection, and again months or years later during routine operation. The question is always the same: when the fire happens at 2:17 AM, will this door close, and will it hold?

Pattern, Not an Outlier — Other Recent Fires and What They Suggest

The Quezon City tragedy was not an isolated event. In Binondo, Manila’s Chinatown, a mixed-use building burned for nearly three hours before firefighters regained control, leaving multiple fatalities and severe structural loss. The building combined residential spaces with small commercial storage, a common arrangement in dense urban districts. Firefighters reported blocked hallways, accumulated goods in stairwells, and no effective compartmentation. Once again, the escape routes failed first, and once those routes failed, the building had no time left to give anyone inside.

Similar concerns have surfaced in Cebu, where the Provincial Capitol complex was cited for fire safety violations, including obstructed egress paths and missing or non-functional protective door systems. In Davao, local BFP teams have conducted house-to-house fire safety inspections under Oplan Ligtas Pamayanan, emphasizing that safe escape depends not only on alarms and extinguishers, but on keeping evacuation corridors separated from fire and smoke long enough for people to use them.

When you look across these incidents, a pattern emerges that goes deeper than individual mistakes. The issue is not simply lack of equipment or outdated construction. The real challenge is continuity: the way buildings are modified, lived in, adapted, and negotiated over time. A corridor designed to be part of a protected escape route can gradually turn into an extended living area, a storage hallway, or a ventilation path. This is not unique to the Philippines—it appears anywhere buildings work hard to meet the needs of many people in tight space. But in the Philippines, where wood-based construction, informal renovations, and shared interiors are common, the consequences become visible quickly.

This is also where fire doors re-enter the conversation, not as imported hardware, but as local practice. In several condominium and institutional upgrades in Metro Manila and Central Visayas, our team at YK Door Industry has been involved in projects where the focus was not merely to “install new fire-rated doors,” but to re-establish protected escape paths that had slowly eroded over years of daily use. In these projects, the work was not glamorous. It involved measuring door clearances millimeter by millimeter, documenting closer timing, coordinating hardware compatibility with local emergency exit rules, and training building staff on not propping doors open on hot days. The biggest lesson was that a fire door does not function alone; it only works when the corridor, door, frame, closer, seals, and daily habits work together.

So the question in the Philippines is not whether fire doors are required; the law and the code already say they are. The real question is whether buildings—new and old, formal and adapted—preserve the integrity of these protective lines over time. Fires do not wait for perfect compliance. They simply test whether the building holds long enough for its people to leave.

And in every one of these recent events, the time available was painfully short.

Actionable Checklist for Building Owners, Facility Managers, and Contractors

When discussing Philippines fire door requirements, the conversation often sounds technical: ratings, labels, test reports, certification numbers. But in every real fire incident, the question becomes very simple: Did the door slow the fire long enough for people to get out? A fire door earns its value in minutes, and those minutes come from decisions made long before the fire ever starts. Below is a practical framework based on what we see repeatedly in Philippine residential buildings, schools, hospitals, dormitories, and mixed-use developments.

1. Start With the Path of Escape, Not the Door Itself

A fire door only matters if it protects a continuous evacuation route. Walk your building as if you were escaping from the second floor at 2:00 AM. Does the corridor lead to a stair that is physically separated from living or working spaces? Are there locations where smoke could enter the stair directly? If so, that is where a fire-rated door is not just a legal requirement under RA 9514, but a life-preserving boundary.

2. Confirm the Fire Door Rating and Compatibility

In the Philippines, the rating of a fire door must match the fire-rated wall it is installed in. For example, a 2-hour fire wall requires a 2-hour rated fire door, not simply “a heavy door” or “metal door.” Many buildings fail inspection not because the door is missing, but because the door, frame, hinges, closer, and seals were not tested together as a system. The rating is not about the leaf alone. It is about the entire assembly working under heat, pressure, and smoke.

3. Pay Attention to the Small Things That Decide Whether the Door Works

The difference between a functioning Philippines fire door and a non-functioning one is often measured in millimeters and seconds.

- The gap around the door edges must be controlled; a wide gap can let smoke pass through even if the door is fire-rated.

- The closer must close the door fully and latch it. If it stops short, the seal is lost.

- The door must not be propped open, no matter how hot the corridor feels. This is one of the most common causes of failure in residential and dormitory fires across Metro Manila and Cebu. A fire door held open is a fire door erased.

4. Keep Records and Photographs for BFP Inspection

When the Bureau of Fire Protection inspects, showing that your fire-rated doors were installed correctly matters just as much as having them. Keep simple but useful documentation:

- A door schedule matching locations and ratings

- Installation photos showing frame anchoring and seals

- Closer timing videos (3 full cycles)

- A maintenance log showing quarterly checks

These are the kinds of details that allow a building to pass BFP evaluation quickly and smoothly, and more importantly, they show that the building is operationally safe, not just certified on paper.

5. Train the People Who Use the Building Every Day

The best fire door in the Philippines still fails if someone wedges it open to let air move, or because “the closer makes it too hard to push.” Education matters. In several YK projects in Metro Manila and Central Visayas, the most meaningful step was not installation—it was explaining to residents and staff what the door is buying them: time, breathability, and a usable escape route.

Fire safety is never only a product question.

It is a behavior + design + maintenance system.

And the building only protects people when all three stay aligned.

Why the Discussion on Fire Doors in the Philippines Is Really a Discussion About Time, Space, and Human Behavior

When we talk about fire doors in the Philippines, it is easy to slip into technical vocabulary: ratings, certifications, fire-resistance hours, BFP permit procedures. Yet none of those are what people remember when a fire occurs. What they remember is whether the corridor was usable. Whether the air was breathable. Whether the stairwell door closed behind them. Whether they had time.

Time is the currency in a fire.

And buildings either save time or cost it.

The challenge in many Filipino residential buildings is not a lack of awareness, or even a lack of rules. RA 9514 already defines what must be protected and how. The Bureau of Fire Protection already instructs where fire-rated doors should be placed and how escape paths must be secured. But buildings are not static. They are lived in. They are adjusted for comfort, airflow, convenience, climate, privacy, rent arrangements, shared usage, and daily routines.

A corridor meant to be a protected escape path may slowly evolve into something else: a drying area for laundry, a place for shoe racks, an extension of cooking or social space, or simply a way for air to move in units without air conditioning. In that transition, the fire door moves from being a barrier to being something that feels “in the way.” People prop it open. Someone takes off the door closer one day because it “feels heavy.” The bottom seal erodes. A hinge is swapped for a cheaper one during maintenance. No one notices the difference that each change makes in isolation—but together, they erase the time the door was meant to provide.

So when we speak about Philippines fire-rated door systems, we cannot stop at installation. The real question is whether the building’s daily habits allow the door to remain what it was designed to be. A fire door is not a promise made during construction; it is a promise kept in the ordinary routines of living.

This is something we have seen repeatedly in YK’s retrofit and upgrade projects in Manila and Cebu. The hardest part has never been sourcing the right fire-rated assembly or matching the door to the wall rating. Those are solvable matters. The harder work is quieter and slower: explaining to caretakers why the door needs to close every time; showing staff how to listen to a latch; helping residents understand that a comfortable airflow today should not trade away survivability tomorrow.These conversations are not dramatic. They sound small. But they are the real work. A fire door is a cultural object as much as an architectural one. It embodies a shared understanding that escape routes must remain escape routes, even on ordinary days when there is no smoke, no flame, no reason to think about danger at all.And this is where the lesson from Quezon City lands heavily.Nobody expected the fire.Nobody thought the corridor would become impassable so quickly.

Nobody imagined that escape would require climbing through a bathroom window.When the hallway is still there, everyone assumes it always will be.Until one night, it isn’t.

Conclusion

The fire in Quezon City lasted less than an hour, yet the decisions that shaped the outcome were made years before the flames started: the materials used, the corridors shared, the habits that kept doors open, the missing separations that allowed smoke to move faster than people could react. A fire-rated door is not a luxury item or a bureaucratic requirement. It is a boundary that buys time—time to breathe, time to move, time to survive.

In the Philippines, where buildings adapt constantly to daily life, the challenge is not just installing fire doors. It is preserving their purpose. A hallway must remain a hallway. A stairwell must remain a refuge. A door that was meant to close must be allowed to close. If we can protect the spaces that people rely on in those first minutes, then the next fire will not have the same ending.

The lesson is not dramatic, but it is clear:

Fire safety is not an event. It is a habit.

And a building protects life only when that habit is shared.

FAQ

Q1: How do fire doors help during a fire in the Philippines?

They hold back heat and smoke, keeping hallways and stairwells usable long enough for evacuation. They don’t stop the fire; they slow it to buy time.

Q2: Are all metal doors considered fire doors?

No. A fire door in the Philippines must have a valid fire rating and be installed with a tested frame, hinges, closer, and seals. The system works only as a whole.

Q3: Why do many Philippine buildings fail BFP fire door inspections?

The most common reasons are wedged-open doors, missing closers, non-rated replacements, and gaps too wide to stop smoke. The failure is often in use—not equipment.

Q4: Do old buildings in the Philippines need to replace non-rated doors?

If the corridor or stairwell is part of an evacuation route, then yes. Under RA 9514, escape paths must be separated by fire-rated, self-closing doors.

Q5: What is the simplest improvement if a full fire door replacement is not immediately possible?

Start with restoring self-closing hardware, removing door wedges, and sealing gaps. Even small steps can increase survivability during early fire spread.